The rule at Utah’s Place is, you get one red bag and one plastic bin to store all your stuff. The bag is 2 feet by 3 feet; the bin, 6 inches deep, 2 feet wide, 3 ½ feet long. It’s not much, but it’s more than you get at most shelters, which is nothing. You must place the bag and the bin on your bunk when you leave in the morning, so the caretaker can sweep under your bed.

Another rule is, when you’re gone from the shelter for longer than one day, belongings you leave behind will be placed in large plastic bags that will be dated and stored for 5 days; if you don’t come back to claim your things within that time, important papers and other valuables will be removed and saved, but whatever remains in the bags will be discarded.

These rules got a little lost last winter when our guest population significantly increased.

To get more folks out of the rain and cold, the City of Grass Valley altered Hospitality House’s use permit to allow us to accept 15 more people than we usually shelter. We have 54 beds, and with 69 people everyone felt the strain. At night the dining room became a dormitory where people slept on mats they’d have to quickly fold up and stow before early morning breakfast the next day. The 15 weren’t always the same people; folks came and went. Each person had belongings that were placed in 30-gallon black plastic bags and stored on shelves in the upstairs lounge.

Our 54 guests also came and went, and when they weren’t there their things, too, were added to the pile. One day I went upstairs and saw scores of bags lining the hallway and stuffed into the lounge, which is supposed to be a peaceful, orderly common room where guests can relax in the evening.

It took me and two strong men all of one afternoon to go through these bags, figure out whose were whose, label the keepers, and discard the abandoned. One woman, a fashion aficionada with a good eye who could identify specific designer brands from across a parking lot, had 19 bags filled with thrift store finds. She was given 7 days to get a storage unit and move her wardrobe into it. No one else had as much as she did, but many had suitcases, cardboard boxes, giant heavy-duty plastic crates, and God knows, plastic bags of every conceivable description.

After 7 days, when we had that stuff under control, I turned to a much harder task: asking folks to remove everything from their beds that didn’t fit into one medium-sized red bag and one plastic bin of very modest proportions. I began in the men’s dorm with a bunk belonging to a young student at Sierra College whom I’d often observed on the street, lumbering along under a stupendous backpack. His bed contained a vast omnium-gatherum: two large suitcases, three huge cardboard boxes full of books, multiple brown paper bags full of clothes, several clear plastic bags full of clothes, many shoes, paper and plastic bags of packaged food, jackets and coats, and a broken umbrella.

The clothes I saw were rumpled and ragged-looking, and most of the shoes were down at heel. The books had come from one of three places: school, church, or the library. He was obviously supplementing his college curriculum with a well-rounded selection of books from the fields of history, philosophy, psychology, science, and literature. There were some fabulous oversize art books, too, and a smattering of fantasy thrown in for fun.

We took our time figuring out what among his possessions to keep and where the excess could go. My young scholar listened to me thoughtfully and accepted my systematic pawing through his belongings with dignity. He explained what everything was and why he needed it, while I explained why he couldn’t have most of it there in an emergency shelter shared by 53 (let alone 68) other people. In the end, with bowed head, he declared his willingness to ask his brother to come pick up everything that wouldn’t fit into the bag and bin.

Much of the time, as I proceeded with the other 53 beds, I felt like an authoritarian jerk. I cross-examined myself constantly to make sure I believed my own story about the necessity to have everything neat, clean, and the same. I made exceptions for four things: Bibles, addiction recovery books, stuffed animals, and one man’s framed picture of his lovely little boy.

At a homeless shelter, power is wielded in one-up, one-down relationships in which staff members, volunteers, and board members have power over guests. The shelter has 40 rules enumerated in a formal document guests must read and sign. These rules, developed and revised over the years, provide a blueprint for behavior that keeps everyone safe. Any guest who thinks a rule has been enforced unfairly may make a formal appeal to the director—several have done so successfully.

Some years ago when I was a monitor seeing to people’s needs and enforcing these rules, my most common dispute with our guests was about movies. We had to outlaw those that depicted violence, but they would inevitably turn up, and every time they did I had to shut them off and deal with the consequent cries of indignation. “We’re adults!” someone would yell. “You treat us like children!” They were right, and all I could offer was the usual institutional justification: we had to consider the good of the group as a whole. Someone could be triggered by the sounds and sights of violence, especially someone among the war veterans and domestic violence victims whom we try to keep safe from experiences that ignite memories of their explosive pasts. I understood that, but I also felt like an ass every time I had to shut a movie down.

With people’s possessions, it was a hundred times worse. “Homeless people don’t have very much, and you’re making them get rid of what little they have,” people would say—not only guests, but others I spoke to about the problem. “At least we’re giving them time to find an alternative place to put their things,” I would answer. “Some of them have no alternative!” “We’ll work to figure that out,” I would counter. But it was true: sometimes—though, I must say, surprisingly rarely—there truly was no alternative.

One middle-aged man had bags and bags of old clothes and what I considered trash loaded on his bed and even stuffed under his mattress. Coats and jackets and pants and shirts and scarves and old magazines and torn papers and toothpicks and little plastic figures with no heads. “Really I’m an artist,” he said. “I need these things for a project I’m going to do.” In the afternoon he would sit at the dining room table with a pile of torn-out magazine pages, magic markers, and little indescribable pieces of miscellany, drawing or just moving things around. Often a circle of plastic bottles and half-empty paper cups surrounded these things like a high-walled fortress.

His was the most difficult bed of all to clear off. I spent a long time with him, standing there like his mother, watching him while he picked up each item and decided if he could bear to part with it. He had a way of looking down at the floor while casting soulful eyes up at me, kind of shyly, kind of shame-facedly, and maybe kind of manipulatively—I never really understood what that look meant. I may have gotten a clue once, though, when he asked me not to stand over him as he was sorting through his stuff. When I moved away a little, he gave me the look and said, “Thank you, ma’am.” I urged him to call me by my name, but he shot back, “I’ll call you ‘boss,’ because you can tell me what to do.” That hit hard: boss is a bad word in my family (double s.o.b. spelled backwards, Utah used to say). But he was right: I could tell him what to do.

He was right about another thing too. He was an artist. He wasn’t creating much art just then, but he obviously had his visions. In another set of circumstances, in a kinder, most just culture, he may have flourished.

When we first opened Hospitality House in 2005, all I wanted was to help some homeless folks have a place to be at night. I didn’t think about the power dynamic that would pin me toward the top of a hierarchical structure, compelled to tell a group of adults when to wake up, what movies to watch, and where to put their belongings. I wanted power, all right, but only for the good parts: the bed, the showers, and the nourishing food.

One question I commonly heard was, “What would you do if you had to put all your possessions in a bag and a bin?” And the old standby I’ve heard so often over the years, “Utah would turn over in his grave if he knew what was going on.”

I asked myself, What would I do if I lost my home, had no money for a storage unit, and had to go to a shelter—even one as benign as Hospitality House? I’d be devastated. Whatever I was able to keep, I’d cling to. If it wore out, I’d get a replacement and cling to that. The thought reminded me of Utah’s backpack, stored in the basement and still loaded with gear decades after he’d stopped riding the freight trains. Smaller than the shelter’s red bags, it was made of beat-up, stained, light-colored leather and loaded with little compartments and strings to secure belongings like a sleeping bag and an old enameled tin cup. He’d removed whatever clothes he’d had inside, but the things that had kept him going remained: the cup, a tiny cylindrical stove, some rope, a knife, waterproof matches, a chipped enamel plate, and a knife and fork that were attached to each other, hobo-style.

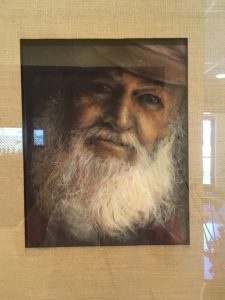

One evening a guest and I had carried our bag debate from the women’s dorm downstairs to the front hall. She was a quiet, self-contained young woman living with some cognitive challenges. She had a job in a fast-food restaurant and was doing everything she could to save money to get herself a place to live. I admired her and was feeling more like an ass than ever, but she had two red bags on her bed, not one. We’d been tussling over that for days, and this evening neither one of us could let it go. She felt that I was being unfair and expressed her sense of injustice with a quiet dignity that tore me up. Earlier, someone had once again mentioned Utah in his grave, and as I stood in the hallway I looked over at his portrait hanging on the wall nearby.

What would he have done about this sweet, strong woman with the extra red bag? Probably he’d have reached for his guitar and sung her a song, or made her laugh with a joke—cut through the tedium of it all with words that were kind and actually funny. The thought brought me into my heart, and from that truer place I apologized to her for any offense I may have committed and recalled the good relationship we’d had before getting mired in all this stuff about bags and bins. Her response was only a nod and a shy smile, but the next day the extra bag was gone. And a week later she herself was gone, having finally achieved her goal of moving into a place of her own. Every time I contemplate the often painful necessity of keeping things safe at the shelter, I have to remember that it was Hospitality House that helped her do that.